Fannie & Freddie’s Fate: 4 Paths, 1 Industry on Edge

March 21, 2025

The appointment of Bill Pulte as the new director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) — followed swiftly by his dismissal of multiple executives at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — has reignited national debate over the fate of these two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). As key pillars of the U.S. housing finance system, any changes to their structure will have ripple effects across the mortgage industry.

Two theories dominate the discourse: that Fannie and Freddie will either be merged into a single super-agency or privatized. However, the landscape of possibilities is broader — and each path forward is fraught with legal, operational, and financial complexity.

Four Plausible Futures for the GSEs

🏦 1. Merger into a Single Entity

Concept: Combining Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could streamline the secondary mortgage market, reduce operational redundancies, and simplify loan eligibility standards for lenders.

Legal Viability: Both were established under separate congressional charters — the National Housing Act (1938) for Fannie and the Emergency Home Finance Act (1970) for Freddie. Merging them would require Congressional action to consolidate their charters and governance structures.

🧰 Lender Impacts:

- Operational Disruption: Transitioning to a merged system would necessitate retooling LOS platforms and integrations currently dependent on DU (Fannie) or LPA (Freddie). This could create friction during implementation.

- Guideline Confusion: Lenders would need to retrain staff, recalibrate pricing engines, and ensure regulatory compliance during the transition.

- Loss of Competitive Shopping: Today, lenders often toggle between DU and LPA to secure the best outcome for borrowers. Merging the two would eliminate this flexibility, potentially narrowing the range of favorable loan outcomes.

- Long-Term Streamlining: Eventually, standardized processes could reduce compliance burden, simplify disclosures (e.g., via Vallia Disclose), and enhance interoperability in LOS/CRM systems.

🏢 2. Privatization of Fannie and Freddie

Concept: This path involves transitioning the GSEs back to shareholder control, removing the implicit federal guarantee, and turning them into fully private entities competing in the secondary mortgage market.

Legal Viability: The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA) allows the FHFA to act as conservator, but not to privatize the entities unilaterally. Congressional approval is essential to unwind conservatorship and amend federal charters.

🧰 Lender Impacts:

- Rising Costs: Without government backing, private investors would demand higher risk premiums. Guarantee fees could increase significantly, raising mortgage rates for borrowers and compressing lender margins.

- Reduced Access to Capital: The liquidity provided by the current GSEs may evaporate for non-conforming and higher-risk borrowers, shrinking loan pipelines and limiting product availability.

- Fragmented Compliance: Private GSEs may enforce proprietary guidelines. Lenders could face a tangle of varied underwriting standards, requiring systems like Vallia Data Connect to bridge gaps between LOS and CRM.

- Counterparty Risk: A fragmented market raises fears about credit risk concentration, requiring lenders to strengthen analytics and capital reserve management.

- Service & Affordability Risk: Low-income, rural, and first-time borrowers may be sidelined as private capital prioritizes profitability over public policy goals.

⚖️ 3. Hybrid Public-Private Model

Concept: This model introduces a tiered structure: private guarantors bear the bulk of mortgage credit risk during stable economic periods, while the federal government serves as a backstop during financial crises.

Legal Viability: Though more feasible under current frameworks, this model still requires Congressional legislation to define capital requirements, oversight structures, and trigger conditions for government involvement.

🧰 Lender Impacts:

- Increased Complexity: Lenders must coordinate with multiple private guarantors, each with their own eligibility, pricing, and risk models. This adds friction in loan origination and secondary market delivery.

- Custom Integration Needs: Tools like Vallia AI and DocFlow become essential to manage multiple risk partners while ensuring consistent validation, pricing, and compliance.

- Upside Potential: Competitive private players could offer more innovative products, create niche financing tools, and push technological advances in automation and AI. Lenders equipped with agile tech stacks will benefit.

- Stability During Downturns: A reliable government backstop would prevent liquidity freezes and allow lenders to keep lending during economic shocks — protecting borrower access and lender viability.

🛑 4. Fully Private Market

Concept: The most extreme transformation would see the federal government exit the housing finance market entirely, leaving it to fully private actors. This appeals to free-market proponents but is the least politically feasible and most destabilizing option.

Legal Viability: Dismantling GSE infrastructure would require full repeal or radical amendment of current housing finance laws — including HERA, the GSE charters, and several oversight frameworks.

🧰 Lender Impacts:

- Liquidity Crisis Risks: Without a central buyer of conventional loans, smaller lenders may be unable to access capital markets affordably or consistently. Large aggregators could dominate.

- Lack of Standardization: The loss of universal standards (like DU/LPA or UCDP) would force lenders to manage dozens of proprietary guidelines, increasing loan cycle time and error rates.

- Customer Disservice: Borrowers would face higher rates, fewer loan options, and longer approval timelines. Tools like Vallia Disclose and Vallia Voice-to-LoanApp would be vital to offset delays with automation and AI-guided processing.

- Widening Inequity: Markets for underserved populations could collapse without government mandates. Lenders may retreat from riskier segments, exacerbating the racial and wealth gaps in housing.

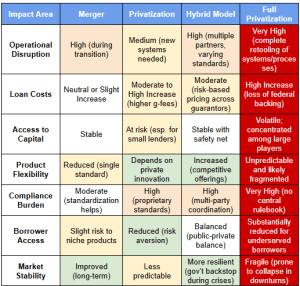

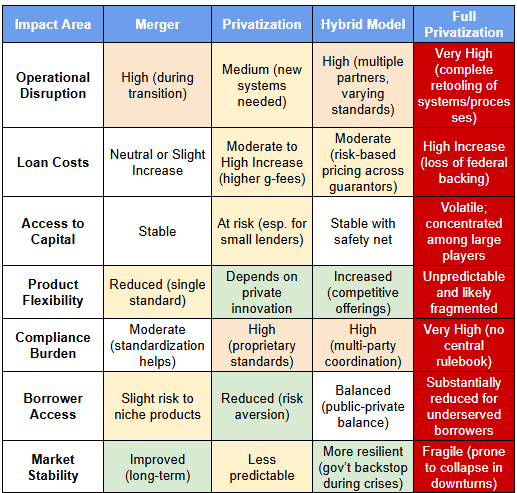

Summary of Lender Options

Legal Framework: Conservatorship and Congressional Constraints

The FHFA, under HERA, has sweeping powers as conservator — but not carte blanche. Any permanent structural changes such as merger, privatization, or liquidation of the GSEs require Congressional authorization. Key statutes include:

- 12 U.S.C. §§ 1716–1723 – Fannie Mae Charter (Federal National Mortgage Association Charter Act) View on GovInfo.gov

- 12 U.S.C. §§ 1451–1459 – Freddie Mac Charter (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation Act) View on GovInfo.gov

- Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA) – Includes FHFA creation, GSE conservatorship framework, and capital requirements Full Text on Congress.gov

- For FHFA provisions specifically, see Title I – Federal Housing Finance Regulatory Reform

Conclusion #1: Navigating the Crossroads

Whether we see a merger, a move toward privatization, or a hybrid risk-sharing model, the outcome will reshape mortgage lending in the United States. For lenders, readiness means more than policy awareness — it demands a future-proof strategy. The truth is, despite all signs indicating that privatization is bad for borrowers and bad for lenders (at least in the near-term), no one can predict where the current administration might go (and why).

Conclusion #2: Despite the Risks, the Current US Government Is Poised to Privatize the GSEs

Position: While the consensus suggests that privatization would harm borrowers and lenders in the near-term, this very adversity may ironically appeal to the current administration’s ideological and political calculus. With Bill Pulte’s high-profile appointment and swift action at the FHFA, there’s a symbolic momentum that signals disruption rather than preservation.

Rationale:

- Populist Disruption: The administration may seek to signal fiscal discipline and reduce government footprint by advocating for GSE privatization, positioning it as a taxpayer protection measure — a narrative that could resonate with fiscal conservatives and populist factions alike.

- Short-term Pain, Long-term Gain Messaging: The government could frame privatization not as an economic blunder, but as a “reset” that forces the private market to innovate, with tools like Vallia Data Connect and Vallia DocFlow poised to bridge the operational chaos by enabling integration and efficiency despite systemic complexity.

- Political Opportunism: A divided Congress may actually make privatization easier to push in pieces — via piecemeal legislation or pilot programs — rather than wholesale reform. This avoids a drawn-out merger debate and lets the FHFA claim progress incrementally.

Conclusion #3: Elon Musk and AI Will Shape the Fate of the GSEs More Than Borrower/Lender Concerns

Position: The future of Fannie and Freddie will be less determined by housing policy and more by tech influence — particularly Elon Musk’s innovation halo and the mainstreaming of AI in financial infrastructure.

Rationale:

- Tech-Driven Regulatory Pressure: As AI continues to outperform legacy underwriting and compliance workflows — evident in tools like Vallia AI Validator, Vallia Disclose, and Vallia Voice-to-LoanApp — regulators may be forced to rethink the centralized GSE model. Automation could make the GSEs redundant or repurpose them into tech-forward data clearinghouses.

- Musk’s Influence on Government Thinking: Musk’s ability to shape public discourse and policy — from EVs to space and energy — could spill into fintech and mortgage tech. If he pushes a vision for a decentralized, tokenized real estate finance ecosystem (think Starlink meets DeFi), policy narratives may shift from preserving the GSEs to leapfrogging them.

- AI Replacing the Middle Layer: With intelligent assistants like Vallia managing applications, disclosures, and borrower communication autonomously, the need for GSE-like aggregation of risk and standardization could erode. AI, not the government, becomes the ultimate underwriter.

Final Conclusion: Rewriting the Rules — A Future in Flux

As FHFA leadership pivots and the GSE debate reignites, the mortgage industry finds itself at a pivotal crossroads. While most experts argue that privatization would disrupt access to affordable credit and upend lender operations in the near term, that very instability may align with the current administration’s political ethos — one that favors disruption over preservation. A push for privatization, despite its risks, could be cast as a bold move toward a leaner federal footprint and a freer market — with tech-powered tools like Vallia Data Connect and Vallia Disclose serving as the operational glue to hold lenders together through the transition.

Yet beyond politics and policy, a more radical possibility looms: that the ultimate shape of the GSEs may be defined not in Washington boardrooms, but through the influence of Silicon Valley’s most ambitious voices and the exponential rise of AI. As automation transforms underwriting, compliance, and borrower engagement, the role of centralized GSEs could be diminished — or entirely reimagined — in favor of a decentralized, AI-first infrastructure. In this vision, AI doesn’t just assist; it replaces. Visionaries like Elon Musk, with the ability to shift national priorities and introduce disruptive models at scale, may play a surprising role in housing finance’s next act.

Thus, whether through political will, technological evolution, or a collision of both, the future of U.S. housing finance may not follow any of the four neatly defined paths. The next chapter won’t just be written by lawmakers and lenders — it will be co-authored by automation, AI, and audacity.